Wilmer Stone mentions on page 66 of his 1910 report to the New Jersey State Museum that Mr. C. F. Saunders reports a trip through the Pines of 1899 in which they passed Munyon Field. I'd always thought Munyon Field was named for the airport now located there. Realized on reading Saunder's report that there were no planes in 1899, thus that it was likely named for someone. A Google search came up empty; a search here resulted in 13 references but nothing about how it got that name. Knowing that the Munyon surname is a Jersey one, was it named for the family that lived out there way back when?

Munyon Field

- Thread starter johnnyb

- Start date

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

The airfield on the south side of NJ 72 east of Jersey Central RR overpass and west of NJ 539, that is used for for fire fighting aircraft.

I think that is called Coyle Field.

http://maps.njpinebarrens.com/#lat=39.81256820347092&lng=-74.42454535167695&z=16&type=terrain&gpx=

http://maps.njpinebarrens.com/#lat=39.81256820347092&lng=-74.42454535167695&z=16&type=terrain&gpx=

Johnny,

Munion Field is in Bass River Township along Oswego Road. As Boyd mentioned you are thinking of Coyle Field.

Munion Field area.

http://maps.njpinebarrens.com/#lat=39.664668029967906&lng=-74.39205307167055&z=14&type=terrain&gpx=

Munion Field is in Bass River Township along Oswego Road. As Boyd mentioned you are thinking of Coyle Field.

Munion Field area.

http://maps.njpinebarrens.com/#lat=39.664668029967906&lng=-74.39205307167055&z=14&type=terrain&gpx=

There is no field at Munion field. The only sign of man I have found there other then the sand roads themselves is considerably south of the crossroads I found a small grassy area under the pines that had one small twisted tree growing in it that was out of place. I think it was a cherry tree and there was a couple of grape vines and on brick laying under the tree. I think this may have been all thats left of Munion Field.

Johnny,

I can't name how many times I have done the same thing.

While looking over my Coyle Field info after your post I found info that I found online and posted years ago. Some may find this interesting. You can still see ruins at both locations.

Guy

July 6, 1938

Officials of the Forest Fire Service of the Department of Conservation and Development are planning the dedication next month of a memorial to the late Colonel Leonidas Coyle, for over 25 years head of the bureau, and known as the "Flying Colonel." The marker will be erected on Route 40, (present day Route 72) about 12 miles below Four Mile Colony. Contributions of forest fire employees will pay for the monument. Ceremonies at the same time will dedicate the bureau's new landing field opposite the recently completed radio tower near the site.

I can't name how many times I have done the same thing.

While looking over my Coyle Field info after your post I found info that I found online and posted years ago. Some may find this interesting. You can still see ruins at both locations.

Guy

July 6, 1938

Officials of the Forest Fire Service of the Department of Conservation and Development are planning the dedication next month of a memorial to the late Colonel Leonidas Coyle, for over 25 years head of the bureau, and known as the "Flying Colonel." The marker will be erected on Route 40, (present day Route 72) about 12 miles below Four Mile Colony. Contributions of forest fire employees will pay for the monument. Ceremonies at the same time will dedicate the bureau's new landing field opposite the recently completed radio tower near the site.

Last edited:

Speaking of Munion Field, does anybod know the history or the reason for the name?

The area is generally known as 5 corners, were their fields or a farm at one time?

The area is generally known as 5 corners, were their fields or a farm at one time?

A most elusive spot for sure. I can't remember where I came to think so, but I believe there was a structure there although I never knew if it was a house or other. There is definitely evidence of former residential activity there. I remember coming across a very old woman's shoe (witch type) when I was there about 15 years ago. I think the structure was located on west side of road junction, in between the 2 roads coming in from west.

A quick Google search brought me right back to an earlier post:

https://forums.njpinebarrens.com/threads/munion-field.3653/

https://forums.njpinebarrens.com/threads/munion-field.3653/

On the 1930 aerial, I can see an outline of what may have once been a field.

The old yard with cherry tree and a couple bricks was right about here. http://maps.njpinebarrens.com/#lat=39.66343743006181&lng=-74.39247149627687&z=17&type=nj2007&gpx=

Looks like a patch of pine amongst oaks which would spell old field.I wonder if that is still visible today?Never noticed it from the road while actively looking for man sign.May have went back to oak by now.

Thanks for the discussion and the old thread. Looking at the satellite view you can see the rectangle of different growth shown in the 1930 aerial. Something was there that history may have forgotten.

Manumuskin

Wouldn't have expected something where you indicate, but the woods are a bit "different" there.

Leave it to Teegate to find a stone or boundary marker, LOL.

Manumuskin

Wouldn't have expected something where you indicate, but the woods are a bit "different" there.

Leave it to Teegate to find a stone or boundary marker, LOL.

To all,A quick Google search brought me right back to an earlier post:

https://forums.njpinebarrens.com/threads/munion-field.3653/

http://library.princeton.edu/njmaps/state_of_nj.html

If you look at the 1868: Geological Survey of New Jersey. Geology of New Jersey (Newark: Daily Advertiser Office, 1868) [Historic Maps Collection].

A road to Munion Field is listed as "new road". Could this be this be the road return cited by Henry Bisbee's work, Sign Posts : Place Names in History of Burlington County, N.J. from 1865?

Willy

I was just perusing the Bass River History Blog and found some additional info on the Munion Field area. It seems that one of the many failed real estate schemes in the pine barrens was attempted at this site as well, called Appleby Estates. Based on the maps posted on that blog entry, it might even be related to the retangular area of disturbed vegetation noted above. http://bassriverhistory.blogspot.com/2013/03/a-journey-to-appleby-estates.html

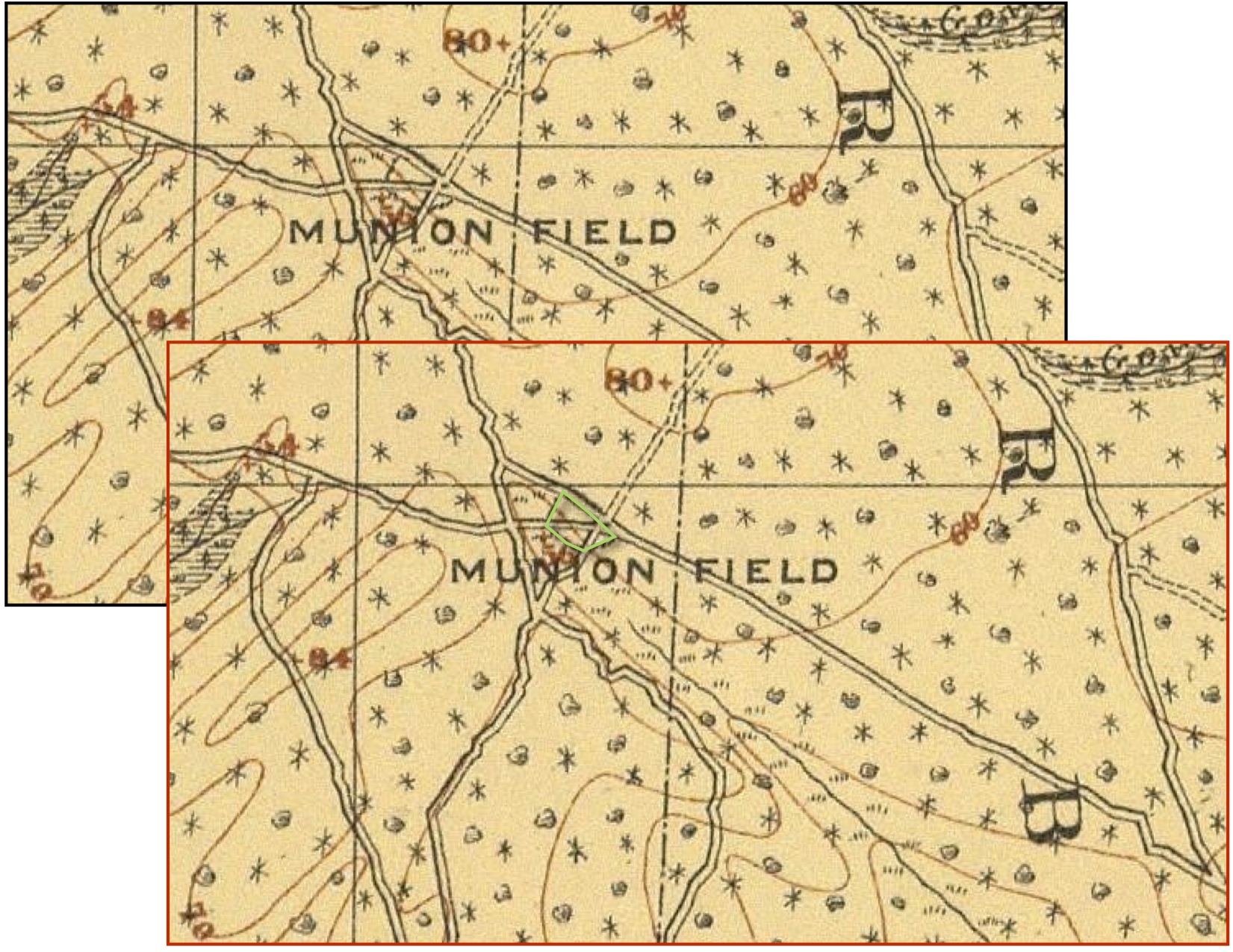

The Cook/Vermeule map seems to indicate a cultivated field (pasture?) was here in 1886:

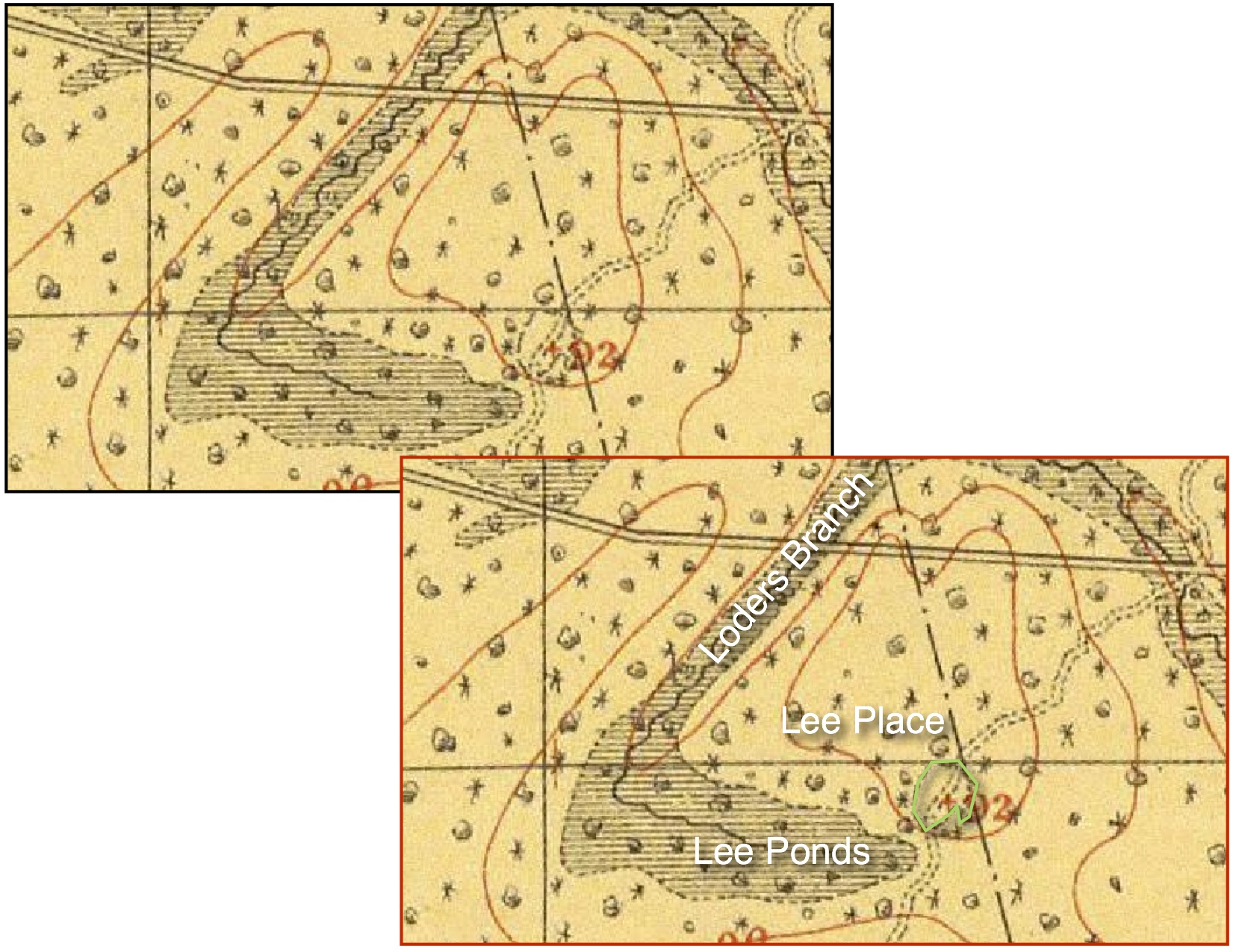

Does that seem right? I am truly astounded at the detail these old maps have. My guess is the Munion Field up there in “North Jersey” could have been associated with charcoal provisioning, not unlike the Lee Place field of similar size behind my house down in “South Jersey.” Dozens of charcoal stations dotted the Pines in support of coaling.

The Lee Place was on a busy trail between Cumberland and Weymouth Furnaces. The track was deeply inset into coversand by wagon traffic, its roadbed worn away to gravel fragipan (dense hardpan-like layer) below. The Lee Place shows up on old maps as bordering Weymouth Furnace land without deed exception. Instead its broken property line might be interpreted as squatter land. A series of Lee Pond spungs provided a means of livestock watering. I suppose Shord Mill Brook may have provided similar use if Munion Field had also served as a charcoal station. More Lee Pond details are provided at bottom of this page:

S-M

Does that seem right? I am truly astounded at the detail these old maps have. My guess is the Munion Field up there in “North Jersey” could have been associated with charcoal provisioning, not unlike the Lee Place field of similar size behind my house down in “South Jersey.” Dozens of charcoal stations dotted the Pines in support of coaling.

The Lee Place was on a busy trail between Cumberland and Weymouth Furnaces. The track was deeply inset into coversand by wagon traffic, its roadbed worn away to gravel fragipan (dense hardpan-like layer) below. The Lee Place shows up on old maps as bordering Weymouth Furnace land without deed exception. Instead its broken property line might be interpreted as squatter land. A series of Lee Pond spungs provided a means of livestock watering. I suppose Shord Mill Brook may have provided similar use if Munion Field had also served as a charcoal station. More Lee Pond details are provided at bottom of this page:

S-M

Last edited:

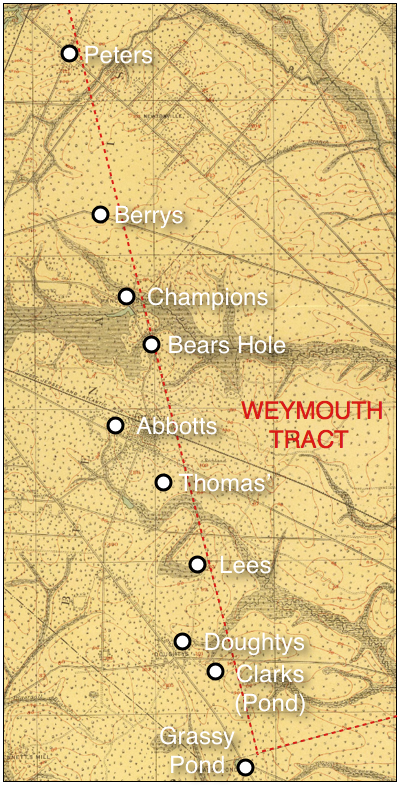

Does Munion Field border a large furnace tract? Here's a figure I put together of places associated with coaling along Weymouth Tract's western edge (red dash), although the funace owned land beyond the classic tract border. I see the stations as last-exit truck stops before you enter furnace land. Each place is rich in Pinelands lore. Lee Place was also home to Billy Adams, a classic bearded dark-coated hermit also known as Five-Acre Farmer. It is also the site of several studies I published on spung geology (French & Demitroff 2001, Demitroff et al. 2007). Lee Pond's bottom had evidence of cryogenic weathering of silicates that matched that of polar Siberia.

S-M

S-M

Last edited:

Folks:

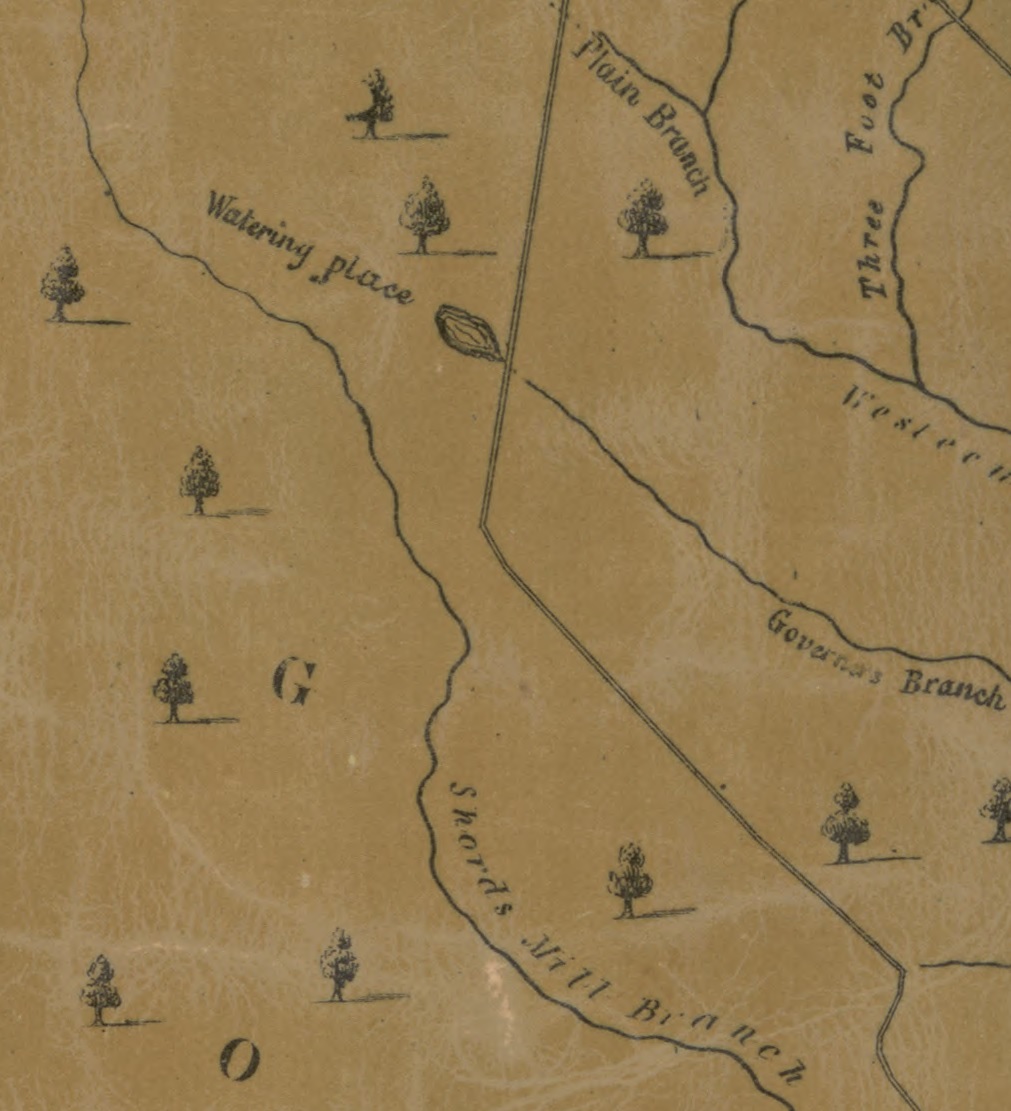

I think Mark is on to something with his analysis of Munion Field. As a toponym, it does not appear until the 1865 road return referenced in Doc Bisbee’s book, Sign Posts. I hope to obtain a copy of that road return in the near future. Munion Field does not appear as a label on the 1849 or the 1859 map of Burlington County. The latter map, however, does include the label “Watering Place” at the end of Governor’s Branch of Westecunk Creek:

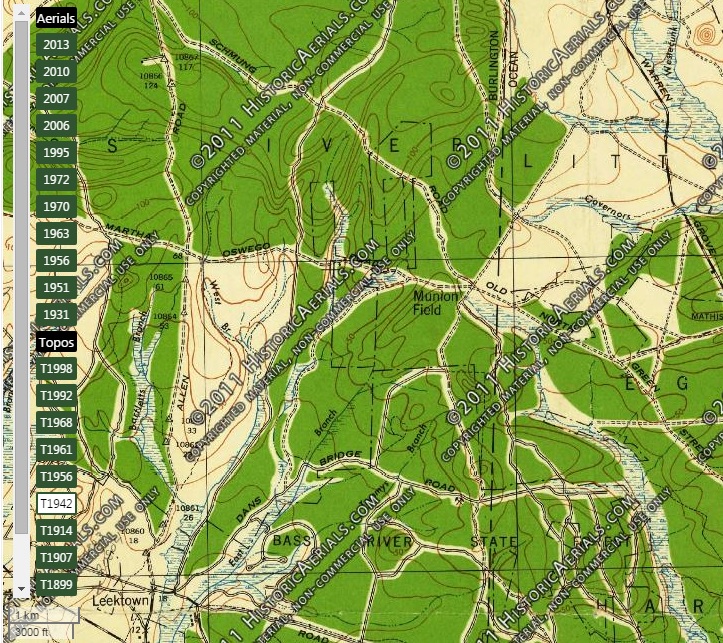

Combine this with the old name for the road passing Munion Field—Martha-Oswego Road—and it makes perfect sense that Munion Field served as a stopping point, and maybe a provisioning location, for the colliers working to supply Martha Furnace with its insatiable appetite for charcoal. Here is a detail from the 1942 USGS topo showing Munion Field and the road names:

In reviewing Bisbee’s version of the Martha Furnace Diary, there are two members of the Lemunion (and all of its spelling permutations!) family working for Martha: David and John. While Bisbee’s lists in the back of the book feature both men as colliers in 1809, only David appears as a collier in the actual diary. So, Munion field could very well have belonged to either David or John, but a bit of title work will be needed to confirm this posit. With the Watering Place nearby, as well as the headwaters of Shord’s Mill Brook, the teamsters on the coal-boxes would have the opportunity to water their horses. I should also point out that a John Munyon Jr. operated a tavern down in Gloucester County, so it is possible that he or his father, perhaps the John that worked for Martha, operated an unlicensed jug tavern at Munion Field. By 1870, David Lemunion resided in Stafford Township, Ocean County, and died there circa 1877.

In the 1900 edition of the Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia, C.G. Saunders published an article titled, “The Pine Barrens of New Jersey.” In the article, we find the following passage:

A forty-mile trip in midsummer across the Pine Barrens has drawbacks enough to make even the most enthusiastic flower-lover think twice before entering upon it. The sands are heavy, the flies and ticks and mosquitoes are numerous, the heat is excessive, springs are few and far between, and forest fires are apt to be at their devastating work in the very place to be visited. However, we decided to chance these things, and on the evening of July 3, 1899, found ourselves landed at an old-fashioned hotel at Tuckerton, and bargaining with a resident South Jerseyman—half farmer, half sportsman, and altogether a pioneersman, to use his own expression—for a team to take us across to Atsion with board and lodgingenroute,and the next morning bright and early we were jogging along the road that leads from Tuckerton northwest toward the Lower Plains.

Mile after mile of oak and pine barrens were passed without sign of human habitation, and when five miles were registered we came to the spot which is marked upon the maps as Munyon Field, Here, in old times, had been a house, and a family had lived here, scratching some sort of a living from the sand and fattening hogs on the abundant mast which strewed the ground under the little chinquapin oaks. Now no vestige of human occupation remains save a little clearing which is rapidly filling up with wildingsfrom the surrounding forest, prominent among them that characteristic primrose of the Pine Barrens, Oenothera siuuata L.

Good sleuthing, Mark. I’ll save the debate over “North Jersey” and “South Jersey” for another time!

Best regards,

Jerseyman

I think Mark is on to something with his analysis of Munion Field. As a toponym, it does not appear until the 1865 road return referenced in Doc Bisbee’s book, Sign Posts. I hope to obtain a copy of that road return in the near future. Munion Field does not appear as a label on the 1849 or the 1859 map of Burlington County. The latter map, however, does include the label “Watering Place” at the end of Governor’s Branch of Westecunk Creek:

Combine this with the old name for the road passing Munion Field—Martha-Oswego Road—and it makes perfect sense that Munion Field served as a stopping point, and maybe a provisioning location, for the colliers working to supply Martha Furnace with its insatiable appetite for charcoal. Here is a detail from the 1942 USGS topo showing Munion Field and the road names:

In reviewing Bisbee’s version of the Martha Furnace Diary, there are two members of the Lemunion (and all of its spelling permutations!) family working for Martha: David and John. While Bisbee’s lists in the back of the book feature both men as colliers in 1809, only David appears as a collier in the actual diary. So, Munion field could very well have belonged to either David or John, but a bit of title work will be needed to confirm this posit. With the Watering Place nearby, as well as the headwaters of Shord’s Mill Brook, the teamsters on the coal-boxes would have the opportunity to water their horses. I should also point out that a John Munyon Jr. operated a tavern down in Gloucester County, so it is possible that he or his father, perhaps the John that worked for Martha, operated an unlicensed jug tavern at Munion Field. By 1870, David Lemunion resided in Stafford Township, Ocean County, and died there circa 1877.

In the 1900 edition of the Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia, C.G. Saunders published an article titled, “The Pine Barrens of New Jersey.” In the article, we find the following passage:

A forty-mile trip in midsummer across the Pine Barrens has drawbacks enough to make even the most enthusiastic flower-lover think twice before entering upon it. The sands are heavy, the flies and ticks and mosquitoes are numerous, the heat is excessive, springs are few and far between, and forest fires are apt to be at their devastating work in the very place to be visited. However, we decided to chance these things, and on the evening of July 3, 1899, found ourselves landed at an old-fashioned hotel at Tuckerton, and bargaining with a resident South Jerseyman—half farmer, half sportsman, and altogether a pioneersman, to use his own expression—for a team to take us across to Atsion with board and lodgingenroute,and the next morning bright and early we were jogging along the road that leads from Tuckerton northwest toward the Lower Plains.

Mile after mile of oak and pine barrens were passed without sign of human habitation, and when five miles were registered we came to the spot which is marked upon the maps as Munyon Field, Here, in old times, had been a house, and a family had lived here, scratching some sort of a living from the sand and fattening hogs on the abundant mast which strewed the ground under the little chinquapin oaks. Now no vestige of human occupation remains save a little clearing which is rapidly filling up with wildingsfrom the surrounding forest, prominent among them that characteristic primrose of the Pine Barrens, Oenothera siuuata L.

Good sleuthing, Mark. I’ll save the debate over “North Jersey” and “South Jersey” for another time!

Best regards,

Jerseyman